Can I use a metric as a loss function?

Difference between loss and metrics.

- What is a “loss” function?

- What are metrics?

- So what is the difference?

- Can I use the loss function as my metric?

- Can I use my metric as the loss function?

- Is it clearer now ?

What is a “loss” function?

Optimization algorithms try to optimize an objective function either by maximizing it or by minimizing it.

A loss function is by convention an objective function we wish to minimize.

“A loss function or cost function is a function that maps an event or values of one or more variables onto a real number intuitively representing some “cost” associated with the event. An optimization problem seeks to minimize a loss function.” (Wikipedia)

In other words, the loss function will return a smaller number for a better model.

What are metrics?

A metric is a function that is used to judge the performance of our model.

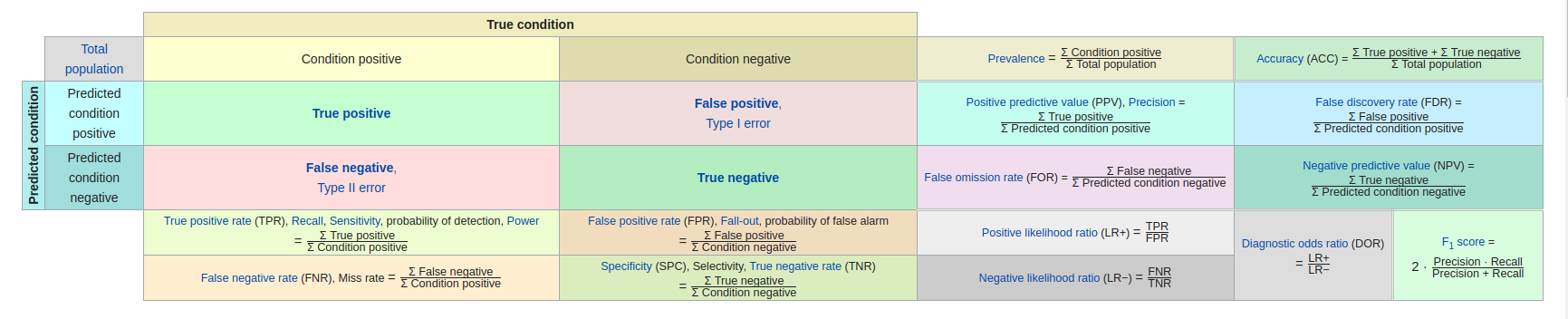

Some well known metrics for classification:

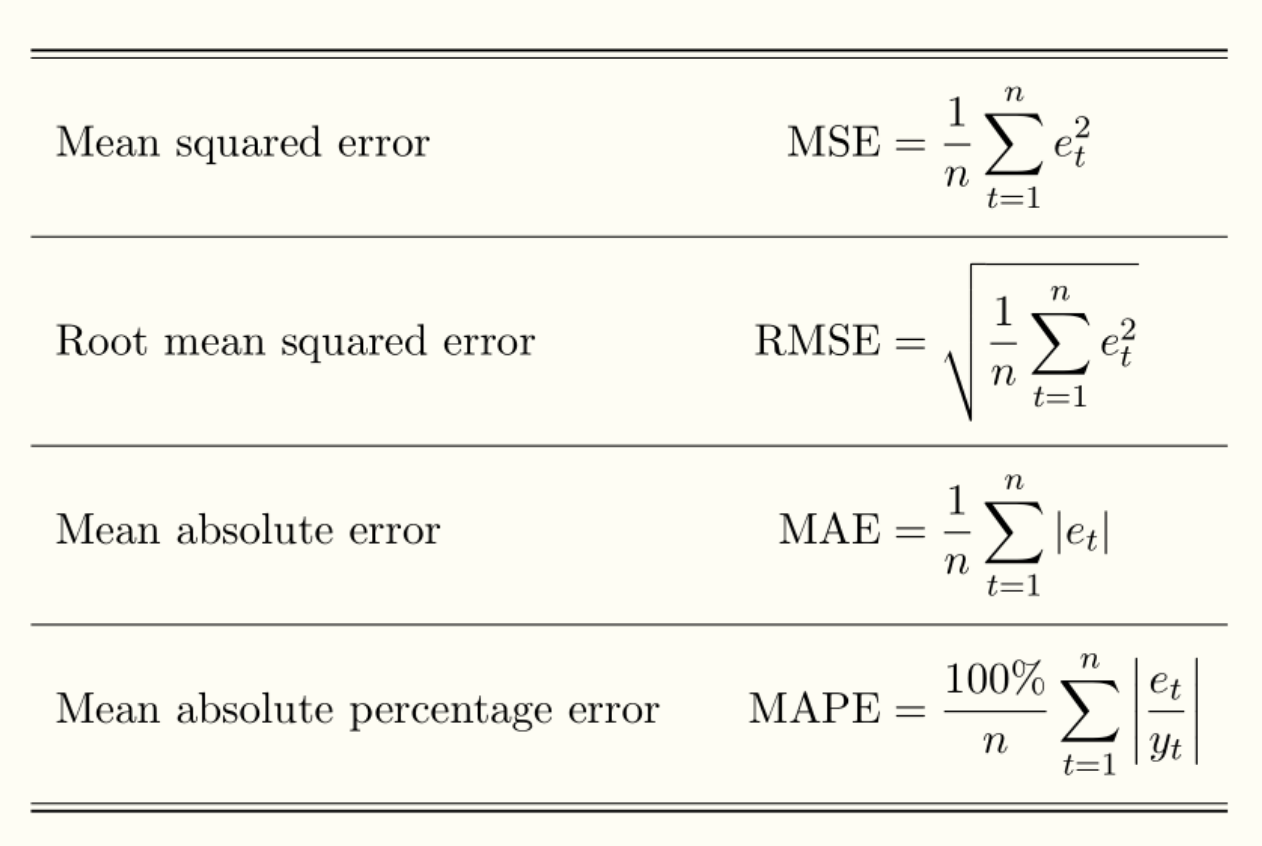

Some well known metrics for regression:

Choosing metrics representative of the problem at hand and what matters isn’t always obvious.

Take the example of building a model that classifies whether Yes or No a patient with COVID-19 should be sent to intensive care, using supervised learning on a labeled dataset built from real world data. Miss rate (also called False negative rate) would be a good metric since you really want to the amount of times you predict No falsely to be minimal. Lives are at risk ! You may also want to take a look at your Fall-out (False positive rate) to avoid saturating the intensive care unit with people that don’t need it.

So what is the difference?

The loss function is the function your algorithm tries to minimize and the metric is what you evaluate your model on. You will always need a metric to evaluate your model but particular algorithms will rely on a separate loss function during training, often as a proxy.

Can I use the loss function as my metric?

Here we are talking about loss functions that actually work for your particular algorithm. As you will see later, not all metrics can be used as a loss function.

You can, except…

Sometimes, loss function values can be confusing and hard to interpret.

For example, if you use cross-entropy loss on a classification problem and get an output value of 2, you know it is better than 2.5 since you want to minimize it but how do you know if a loss of 2 or an improvement of 0.5 is actually any good?

That’s when metrics come into play.

Metrics are defined for human consumption and are what you care about when evaluating your model.

Otherwise it is fine

Sometimes your loss function can be used as a metric, meaning it is being minimized by the algorithm and humans can interpret its outputs easily.

An example would be Root-Mean-Square error.

Can I use my metric as the loss function?

Not always!

You can’t, for several reasons

Some algorithms require the loss function to be differentiable and some metrics, such as accuracy or any other step function, are not.

These algorithms usually use some form of gradient descent to update the parameters. This is the case for neural network weight stepping, where the partial derivative of the loss with respect to each weight is calculated.

Let’s illustrate this by using accuracy on a classification problem where the model assigns a probability to each mutually exclusive class for a given input.

In this case, a small change to a parameter’s weight may not change the outcome of our predictions but only our confidence in them, meaning the accuracy remains the same. The partial derivative of the loss with respect to this parameter would be 0 (infinity at the threshold) most of the time, preventing our model from learning (a step of 0 would keep the weight and model as is).

In other words, we want the small changes made to the parameter weights to be reflected in the loss function.

Some algorithms don’t require their function to be differentiable but would not work with some functions by their nature. You can read this post as an example of why classification error can’t be used for decision tree.

It may not be ideal

Some objective functions are easier to optimize than others. We might want to use a proxy easy loss function instead of a hard one.

We often choose to optimize smooth and convex loss functions because:

- They are differentiable anywhere.

- A minimum is always a global minimum.

Using gradient descent on such function will lead you surely towards the global minima and not get stuck in a local mimimum or saddle point.

There are plenty of ressources about convex functions on the internet. I’ll share one with you. I personally didn’t get all of it but maybe you will.

Some algorithms seem to empirically work well with non-convex functions. This is the case of Deep Learning for example, where we often use gradient descent on a non-convex loss function.

Another thing you need to be careful of is that different loss functions bring different assumptions to the model. For example, the logistic regression loss assumes a Bernoulli distribution.

Sure go ahead

If your metric doesn’t fall into the limitations mentioned above then go ahead ! Optimizing directly on what matters (the metric) is ideal.

Is it clearer now ?

Did I help clear things up or is it even more confusing now? Or am I mistaken somehow? You can share your questions / remarks regarding the subject by writing a comment or annotating the text using Hypothes.is!